The Theory of Violence

On the violence inhibition mechanism or why, even though normally people have a strong inner resistance to harming others, some find it easy to commit violence and even kill, and how to solve this problem

When it comes to violence, although it seems to be a socially unacceptable phenomenon, its naturalness is most often not questioned, considering the fact that we can observe it in the animal world and human society. However, if we study this phenomenon more deeply, we can easily realize that things are not so simple, especially in the case of intraspecific interactions.

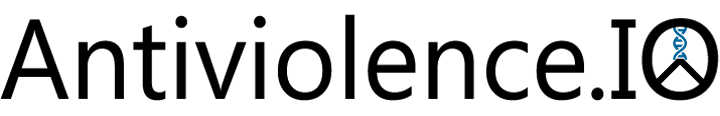

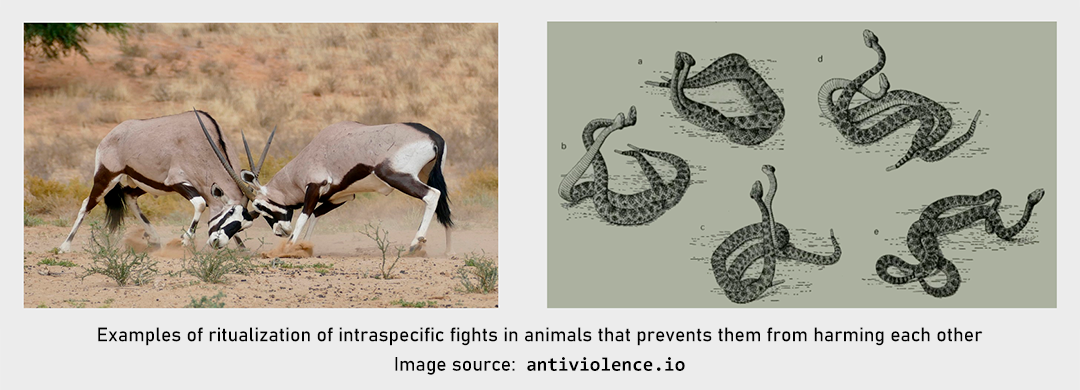

Did you know that in the nervous system of many animals and even humans, there is a mechanism that, when activated, inhibits offensive aggression towards members of their own species while not affecting defensive behavior or other forms of activity? The theory that many species have inhibitions of intraspecific aggression has existed for quite a long time, since the very emergence of ethology, which is the science of animal behavior. In many cases, and especially when members of the same species have strong innate weapons and no opportunity to avoid each other, unrestrained forms of aggressive behavior reduce the aggressor's own chances of survival and reproduction. This is how aggression inhibitions that prevent the infliction of harm, often through the ritualization of intraspecific fights, emerge during biological evolution.

Similarly, humans have the violence inhibition mechanism. It is based on an innate reflex that causes an aversive reaction when observing the suffering of others. Also, the functioning of this mechanism explains the development of empathy and different aspects of morality, and its dysfunction explains the emergence of psychopathic tendencies, which, according to a huge number of criminological studies, are the purest and the best explanation of antisocial and violent behavior, especially in the case of premeditated acts of harming people. A lot of evidence, including the findings of anthropologists and military experts, suggests that the average and healthy individual has a strong inner resistance to killing other people. The concept of the violence inhibitor is also supported by research from the fields of psychiatry, neurophysiology, and genetics.

In turn, the prevalence of violence we observe can be explained by the fact that even a relatively small number of individuals who can easily commit it are capable of causing significant harm to other people and society. The truth is that violence is nothing more than a deviation and pathology, and we will get acquainted with all the details and evidence behind such a conclusion. Also, we will develop potential solutions to the problem of still-existing violence in society and human relationships.

You can view a brief presentation of the most important ideas published on this website or continue reading here to learn all the details immediately.

I. Definition of important concepts

In order to study the topic of violence as a form of behavior and social communication, we need to give this concept a concrete definition. Moreover, we will often use the concept of psychopathy, and we must be clear about which state of the human psyche it describes.

1. An ethological approach to the definition of violence

In defining the concept of violence as well as another important concept of self-defense, we will start with the broader concept of aggression. An ethological approach will help us solve this problem. Aggression is a natural disposition to behave aggressively, i.e., in a hostile and unfriendly manner[1][2]. However, functional (or adaptive) aggression as a form of behavior and social communication in intraspecific relationships is characterized by constrained actions, reactions, and social signals between participants in the conflict. It is important to pay attention to this “constraint.” It consists of rules and rituals of a certain magnitude, expression, and sequence, which make aggression functional, dynamic, yet structured behavior within inhibitory limits. Regardless of species-specific rules, these components are necessary for functionally driven aggression[3][4][5]. Also, such inhibition of aggression is the main function of the violence inhibition mechanism, which we will discuss later.

The difference between violence and functional aggression lies in the behavioral sequence or interaction dynamics between two or more conspecifics in combat. Violence is characterized by the absence of inhibitory control and the loss of adaptive functions in social communication. As a quantitative behavior, violence is an escalated, pathological, and abnormal form of aggression characterized primarily by short attack latencies and prolonged and frequent harm-oriented conflict behaviors. As a qualitative behavior, violence is characterized by attacks that are aimed at vulnerable parts of the opponent's body and context-independent attacks regardless of the environment or the sex and type of the opponent[3][4][5][6].

It is believed that functional aggression, unlike violence, is not anticipated to target vulnerable body parts even in the midst of an agonistic interaction unless challenged, as seen in defensive aggression[4][7].

According to the threat superiority effect, humans (like many species) have the ability to quickly and effectively detect threats in the environment, which allows them to activate defense mechanisms in time and adequately respond to the threat. Such a response can be expressed by flight or defensive aggression (it is also called a fight-or-flight response). Threat stimuli can be innate due to the fact that humans have encountered them in the course of biological evolution (for example, snakes) or acquired through experience due to the adaptation of defense mechanisms (for example, a knife or a gun). Threats can be conveyed through many visual or auditory modalities, but in human interactions, they are often indicated through angry facial expressions[8][9][10][11].

Self-defense can be defined as a form of aggression performed in the presence of a threat in the environment and social signals[Author's note]. Also, in the case of intraspecific relationships, self-defense (or defensive aggression) is defined as a form of aggressive behavior performed in response to an attack by another individual. It is worth noting that extreme forms of defensive aggression can have violent characteristics. However, it is distinctly different from offense in terms of its behavioral expression and inhibitory control[12][13].

2. Reactive and proactive aggression

In studies of the human psyche and behavior, the division of aggression into reactive (affective) and proactive (instrumental) forms is widespread. Reactive aggression is an impulsive response to a perceived threat or provocation associated with high emotional arousal, anxiety, and anger. In turn, proactive aggression is instrumental, organized, cold-blooded, and motivated by the anticipation of reward[14][15].

In other words, reactive aggression arises as a reaction of the subject to a certain stimulus (including a threat stimulus that can lead to self-defense) or as a result of frustration. It is limited to a specific conflict, has no intent, and no purpose other than the direct infliction of harm. In turn, proactive aggression consists in achieving a certain positive result by resorting to aggressive actions; it is a planned and motivated act of harming the victim.

Also, it is important to note that proactive aggression is significantly associated with reduced levels of both cognitive empathy, which is the ability to understand the emotions of others, and affective (emotional) empathy, which is the ability to experience the emotions of others[15][16].

3. What psychopathy is and who psychopaths are

Most of us abstain from criminal or violent activities, not only out of fear of being arrested and punished but out of knowledge of the guilt and remorse we will suffer as an outcome and out of the empathy that we have towards the people who would be victimized due to our harmful actions. Yet, for some people, their minds appear to be configured differently. The emotional barriers that should have been there to restrain them from committing a criminal or violent act are absent or porous; thus, they find it easier to break the rules and hurt others. People with such an affective deficit, and with certain interpersonal and behavioral traits that result from that deficit, are known in the literature as having psychopathy[17].

Psychopathy is a socially devastating personality disorder defined by a constellation of affective, interpersonal, and behavioral characteristics, including egocentricity, manipulativeness, deceitfulness, lack of empathy, guilt or remorse, and a propensity to violate social and legal expectations and norms. Psychopaths are intraspecies predators who use charm, manipulation, intimidation, and violence to control others and to satisfy their selfish needs. Lacking in conscience and in feelings for others, they selfishly take what they want and do as they please, violating social norms and expectations without the slightest sense of guilt or regret[18].

Psychopathy can be divided into primary and secondary factors. Although both factors are associated with antisocial behaviors, hostility, and reduced empathy, primary psychopathic traits predominantly reflect interpersonal and affective characteristics such as grandiosity, manipulative behaviors, superficial charm, a lack of remorse or guilt, and emotional detachment. In turn, secondary psychopathic traits refer to features often portrayed by individuals who are irresponsible, impulsive, incapable of long-term planning, and display erratic behaviors[19].

As we will see later in the third topic of Chapter Two, individuals with high scores of primary psychopathy include managers and CEOs who succeed by deceiving, manipulating, and unfairly exploiting others, police and army officers who commit crimes against humanity (mass arrests, tortures, and murders), and politicians who establish authoritarian and oppressive regimes. In turn, ordinary violent offenders are characterized by significantly increased scores of both psychopathy factors. And their highest scores are observed in the most violent criminals, such as serial sexual murderers.

II. Myths and facts about violence

In this chapter, we will look at the various myths about violence that prevent a full understanding of its nature and the facts that will help us understand it. As ethological, archaeological, anthropological, criminological, military, and other evidence demonstrates, violence, and especially killing, is largely absent from intraspecific animal and human relationships. The average and healthy individual has a strong inner resistance to killing, but the minority of killers is still enough to cause significant harm to everyone else.

1. Are intraspecific killings common in animals

A study of 1024 mammalian species showed that only about 40% of them were observed to have at least occasional lethal violence, i.e., cases of deaths of individuals from aggressive actions by members of their own species (including infanticide, cannibalism, and intergroup aggression). Of course, this figure may be underestimated due to the lack of data, but even after adjusting for this possibility, non-violent intraspecific relationships are still common and prevail over violent ones, especially if we take into account that, according to overall statistics, lethal violence is the cause of death in mammals in only 0.3% of cases[20].

Many researchers have come to the conclusion that most intraspecific aggression is non-lethal, and individuals with techniques that enable them to avoid agonistic situations involving serious possibilities of defeat or injury are evolutionarily successful. Across many species, nonkilling is the default and killing is the exception, the oddity, the unusual. Also, restraints against harming and killing conspecifics are common in animals that have strong innate weapons and lack the opportunity to avoid members of their own species[21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28]. A detailed description of examples of such restraints and why they have developed during biological evolution can be found in Chapter Three.

It is important to note that the natural cruelty of chimpanzees is often greatly exaggerated (as in the works of primatologist and anthropologist Richard Wrangham) when, in fact, most of the violence observed in them is provoked by disturbances caused by intense human intervention in their habitat (e.g., deforestation). Most of the known chimpanzee killings have occurred in two exceptional cases, closely related to human impact and representing only 2% of the entire history of chimpanzee observations, and without these cases, killings would be extremely rare for chimpanzees. There is no significant evidence that chimpanzees have an innate predisposition to kill conspecifics, and the idea that chimpanzee and human wars are identical phenomena with common evolutionary roots is refuted by current research (for example, this is well done by anthropologist Brian Ferguson in his book “Chimpanzees, War, and History: Are Men Born to Kill?“). Also, let's not forget that the closest human relative, the pygmy chimpanzee (bonobo), is widely known for its non-violent nature and complete absence of intraspecific killings[29][30][31].

▶ See also: Are chimpanzees and humans innately predisposed to commit killings and wars?

2. Lethal violence in human history or "The Myth of the Violent Savage"

In researching war and peace, one can easily notice a bias toward exaggerating, overemphasizing, and magnifying warfare in comparison to peace. The belief that human beings have evolved to be natural-born killers or that hunter-gatherer societies are almost always warlike is common among ordinary people and scholars alike[32]. As an example, it is a common claim, taken from the works of scientist Steven Pinker, that in the past, 15% of the population of hunter-gatherer societies died from lethal violence, and in some cases, its level could be as high as 60%. Thus, societies that existed before the emergence of agricultural civilizations with cities and monopoly governments suffered from chronic violence and endless wars[33][34].

However, a study examining 600 human populations shows that only 2% of people have been killed in all of human history, and this includes cases of war and genocide[20]. In the case of hunter-gatherer societies of the past, the level of lethal violence was also only 2%[35]. Some studies argue that the presumed universality of warfare in human history lacks empirical support, and the evidence for its commonality in prehistoric times (such as that demonstrated in “War Before Civilization: The Myth of the Peaceful Savage” by Lawrence Keeley) may be overstated and misleading[36][37]. As anthropologist Brian Ferguson writes, considering all the archaeological evidence for Europe and the Near East, and not just selected cases of violence, one can conclude that the idea that 15% of the prehistoric population died from war is not just false, it is absurd. And there is no evidence that war is an expression of innate human tendencies or a selective force driving human psychological evolution[34][38].

Pinker ignored much of the archaeological evidence that did not align with his argument. One survey of 2000–3000 remains found in France showed that 1.9% of them had projectile wounds, including healed ones. Another survey of 350 remains found in Britain showed that about 2% of them had trauma that could potentially lead to death, and another 4–5% had healed wounds. One more survey of 418 remains found in Serbia and Romania showed that 2.3% of them had signs of violent injury. A study of 2500 adult remains found in Japan showed that 2% of them had signs of potentially violent death. Anthropologist Ivana Radovanovic has looked at 1107 remains from Europe, including all of the cases on Pinker's list, and concludes that you could average out at 3.7% for a low estimate of the level of lethal violence and 5.5% for a high estimate. These results are not even close to Pinker's 15%[38][39][35].

Claims about extremely high levels of lethal violence in prehistoric people are often based on an analogy with the high levels of it in some modern hunter-gatherers. However, a study of 21 nomadic forager societies shows that in 10 of them, only one person committed killings, and in 3 of them, there was no killing at all. Nearly half (47%) of the killings occurred in the Tiwi tribe from Australia, which shows its exceptionality. Also, anthropologist Douglas Fry, after studying the anthropological literature, found as many as 70 nonwarring cultures, including cases of completely non-violent tribes, famous examples of which are the Paliyar (or Paliyan) from South India and the Semai from Malaysia, who do not even hit other people in conflicts or physically punish children[35][40][41]. And researcher Johan M. G. van der Dennen has compiled a list of nearly 200 highly unwarlike cultures, in the case of which wars were absent or mainly defensive[42][32]. In addition, a study of 590 societies from all over the world found that the majority (64%) of cultures are nonwarring or unwarlike[40][43]. And although homicide rates vary tremendously from one society to the next and also change over time within the same society, the vast majority of people never kill or attempt to kill anyone[28].

What also turned out to be false was the claim made by anthropologist Napoleon Chagnon, who studied the Yanomami tribes and is often cited by Pinker, that in tribal societies, men who commit killings should be more reproductively successful (have 3 times as many children) as they eliminate their neighbors from procreation. And since, in the past, all people lived in tribes, this allegedly made a human a natural-born killer. However, the study that makes such a claim has methodological flaws; the difference in the average age between the killers and non-killers studied was more than 10 years, which distorts the result. And even if they were the same age (Chagnon insisted that they were but flatly refused to provide evidence for this), other anthropologists' calculations suggest that such a result would still be exaggerated. Also, it does not agree with the findings of other studies, which show that killers not only have the same number of children as non-killers (and the most bellicose among them have even fewer) but that the children of killers are less likely to reach reproductive age[28][44][45].

It is worth briefly mentioning the issue of cannibalism. It turns out that researchers often mistake cases of ritual consumption of dead relatives (endocannibalism) for cases of consumption of enemies defeated in a war (exocannibalism)[46][38]. Also, the discovery of human remains with marks presumably indicating that they were killed for consumption may, in fact, be explained by attacks by predatory animals or burial practices (in some cultures, this process involved separating the flesh of the deceased from the bones)[29].

In general, there is no reason to think that “simple societies,” in which humans have spent 99% of their existence, are predisposed to kill members of other groups. Of course, some hunter-gatherers with complex social structures make wars, but mobile foragers (simple hunter-gatherers) are not characterized by this. Wars between different groups of people only begin to occur when higher levels of social organization emerge. An expanding state is what can introduce violence into an otherwise peaceful population of foragers or horticulturalists[47][36][31].

3. What kind of people commit violent crimes and harm others

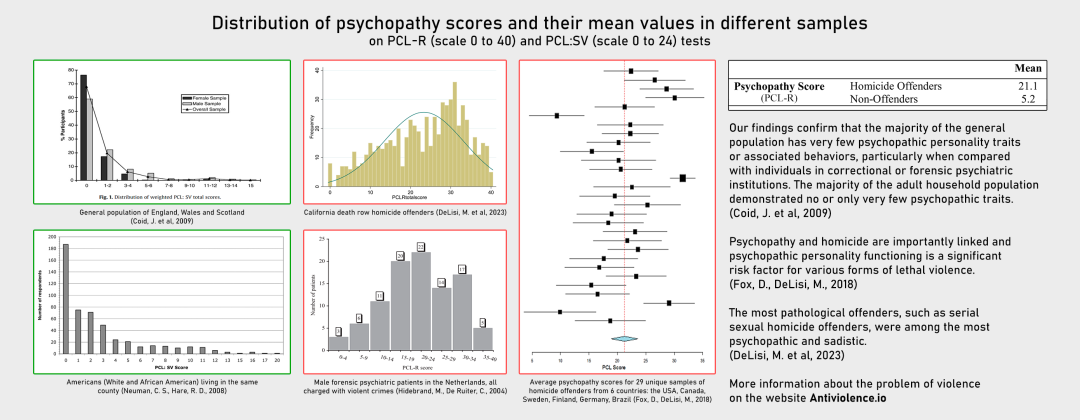

An analysis of 22 studies with 29 unique samples of homicide offenders from 6 countries (USA, Canada, Sweden, Finland, Germany, and Brazil) shows that the mean murderers' psychopathy score on the PCL-R test is 21.1 out of 40. At the same time, for people who do not commit crimes, it is only 5.2[48]. In general, the majority of the population (more than 80–90% of people) demonstrate no or only a few psychopathic traits and associated behaviors. And only 1–2% of people have high psychopathy scores (above 12 out of 24 on the PCL:SV test)[49][50].

In one study of 98 forensic men charged with violent crimes, the mean PCL-R score was 21.4. Only 9 individuals (9.2%) among them had scores below 10[51]. For 636 homicide offenders on death row in California, the mean PCL-R score was 23.31. Only 15% of them scored 10 or less, and these individuals had no official criminal history prior to their capital crimes, were contrite, apologetic, and remorseful during their court proceedings, and generally engaged in normative conduct for the majority of their adult lives. These are people who most would view as “salvageable.” In contrast, individuals with higher psychopathy scores clearly exhibited problem behaviors. And among the five individuals who scored a maximum of 40 points were the most violent criminals, such as serial sexual murderers[52].

Clinical psychopaths, scoring from 25–30 on the PCL-R test and from 18 on the PCL:SV test, make up no more than 1% of people in society. However, as forensic psychologist Robert Hare points out, they make up a significant proportion (up to 25%) of prison populations and are responsible for a markedly disproportionate amount of serious crime and social distress. It has also been found that if people are divided into two equal groups based on their PCL:SV scores, individuals in the higher-scoring group will be 10 times more likely to commit violent crimes[18][53]. The economic burden of crime resulting from psychopathy was up to 7.4% of GDP in the case of the United States as of 2020, and the individual suffering and loss inflicted by psychopaths on others is so enormous that it is likely impossible to estimate[54][55].

An increased number of psychopathic individuals may show up in some professions, for example, managers and CEOs. According to various studies and claims, between 3% and 21% of their representatives are psychopaths[56][57]. Also, one study conducted among employees of companies showed that if a company employs non-psychopathic managers (whose psychopathy scores are less than 9 out of 16 on the PM-MRV test), the overwhelming majority of employees (89.3%) will assess its activities as socially responsible and environmentally friendly. However, this figure drops to 66% in the presence of dysfunctional managers (whose psychopathy scores are 9–12) and to 52.5% in the presence of psychopathic managers (whose psychopathy scores are more than 12). In addition, the majority of employees (79.6%) think that a company shows commitment to them if it has non-psychopathic managers, but this figure drops to as low as 23.7% if psychopathic managers are present. In general, it is a widely known fact that psychopathic individuals working in companies are prone to white-collar crime, such as embezzlement and fraud. They also tend to neglect information security measures. Their actions can often even lead to the company's bankruptcy. These results demonstrate the importance of the problem of corporate psychopaths, who may make ethically questionable decisions in pursuit of their own benefit and have a negative impact on their company and society as a whole[58][59][60][61].

Politicians cannot be expected to do well either; despite the lack of reliable statistics, practically any expert in the field of sociopathy/psychopathy/antisocial personality disorder would not dispute that there is a higher percentage of individuals with psychopathic tendencies among them than in the general population[62]. The mean PCL-R score among army and police officers convicted of crimes against humanity (mass arrests, tortures, and murders) is 21.06. Not only that, they do not have as high scores of secondary psychopathy (which is characterized by impulsivity) as ordinary violent offenders, but they have extremely high scores of primary psychopathy (which is characterized by callousness and lack of empathy). State violators of human rights have an extreme disposition for self-serving, callous, and ruthless treatment of others without guilt or remorse[63]. Psychiatrist Andrew Lobaczewski, in his book “Political Ponerology: A Science on the Nature of Evil Adjusted for Political Purposes,” explains the very emergence of authoritarian and oppressive regimes as the result of the seizure of political power by primary psychopaths[64]. Also, in the case of police officers, primary psychopathic traits may be associated with the use of unjustified and excessive force against criminal suspects[65].

Committing indirect violence, which involves using social manipulation instead of direct physical attack to harm people, also has a significant association with psychopathic tendencies[66]. The same can be said for the use of unethical tactics in business negotiations, such as making false promises, misrepresentation of facts, aggressive bargaining (exerting pressure through emotions and anger), secretly gathering “inappropriate” information about the other party, and attacking their professional network[67]. Psychopathy is also a key factor in the perpetration of intimate partner violence[68][69][70][71]. And the higher an individual's psychopathy scores, the more likely they are to become violent as a result of substance use (alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine)[72]. In addition, psychopathy is a significant risk factor in aggressive religious radicalization, antisemitism and a propensity for extremism (support for the use of violence in achieving political goals)[73][74][75][76][77][78]. And its primary factor significantly predicts an individual's propensity for totalitarian political ideology, expressed by a high need for government-imposed social regulation, acceptance of life under dictatorship, denial of individual freedom, and support for oppressive methods and procedures[79]. Finally, psychopathy traits are associated with carrying guns for illegal purposes (but this does not apply to those whose motivation for carrying a gun is legal) and gun violence[80][81].

Criminologist Matthew DeLisi concludes that psychopathy is the purest and the best explanation of antisocial behavior and can be labeled as a unified theory of crime[82]. It is the most formidable risk factor for antisocial behavior, crime, and violence, and no study exists that has found that psychopathy was unrelated to crime and various aberrant conduct[83]. Also, it is worth noting that the more psychopathic an individual is, the more proactive (instrumental) aggressive behavior can be expected in the crimes they commit. As research demonstrates, committing just one act of proactive violence is already associated with increased psychopathic tendencies of the offender compared to offenders whose actions were reactive (impulsive) or non-violent (as in the case of theft) and non-offenders[84][85][86][87].

▶ See also: How large-scale or political evil arises; The problem of indirect violence; The costs of psychopathy to individuals and society; The relationship of extremism and radicalization to psychopathy and other socially negative personality traits

4. War and resistance to killing

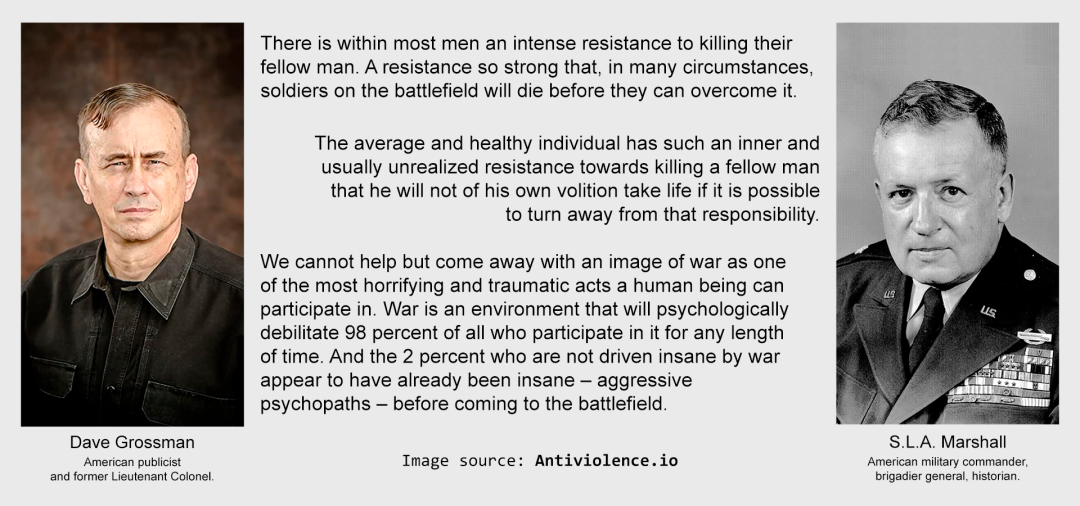

Military experts have found that most humans possess an intense resistance to killing. The resistance is so strong that, in many circumstances, soldiers on the battlefield will die before they can overcome it. There is only 2% of the male population that, if pushed or if given a legitimate reason, will kill without regret or remorse[88][89][90][28]. And we will now familiarize ourselves with the range of evidence behind such a conclusion. Also, along the way, we will examine the criticisms it faces and demonstrate their untenability.

A study by neurologists Roy Swank and Walter Marchand, published after World War II, demonstrated that after 60 days of ongoing battles, 98% of surviving soldiers are psychologically traumatized, and only less than 2% of them who are predisposed to be “aggressive psychopaths” are not affected by such a problem since they apparently do not experience any resistance to killing[91][88][89][90]. Current research also confirms that some traits of primary psychopathy (which is characterized by callousness and lack of empathy) may protect an individual from experiencing psychological trauma as a result of participation in combat[92][93]. In general, almost all combat participants experience it. Military historian Richard Gabriel, who has studied this problem, lists conditions such as fatigue, confusion, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive states, character disorders, and conversion hysteria, including the paralysis of the arm, usually the one used to pull the trigger, seen in soldiers in both World Wars. The traumatic impact of war on the human psyche is also confirmed by the high rate of suicide among veterans[88][90][94][95].

According to American military journalist, Brigadier General, and historian Samuel Marshall, who interviewed 400 infantry companies, only 15–25% of American soldiers fired at enemy positions during World War II. In many cases, those who did not fire were willing to risk great danger to rescue comrades, get ammunition, or run messages. Marshall concludes that the average and healthy individual has such an inner and usually unrealized resistance towards killing a fellow man that he will not of his own volition take life if it is possible to turn away from that responsibility[88][96].

Much criticism has been levied against Marshall, including claims that soldiers actually enjoyed committing killings and accusations that he made up his findings at all. However, historian David Lee shows in his book “Up Close and Personal: The Reality of Close-Quarter Fighting in World War II” that Marshall often visited soldiers after battles and interviewed them regarding firing at the enemy. And the idea that many soldiers enjoyed killing is universally rejected, even by those who were active firers. Most men who participated in combat found killing an unpleasant job, and only a few among the many veterans will claim to have enjoyed it. Many accounts confirm that fighting often depended on one or a few exceptional soldiers who led others in the assault, while the majority merely followed or did nothing[97].

As American publicist and former Lieutenant Colonel Dave Grossman writes, the U.S. Armed Forces have widely accepted these conclusions. Although Marshall's methodology may not meet rigorous modern standards, that does not mean he lied, and every available, parallel, scholarly study validates his basic findings. In support of his words, Grossman cites such war researchers as Charles Ardant du Picq, John Keegan, Richard Holmes, and Paddy Griffith. The evidence they and others provide (some of which we will review after dealing with the criticism) is compiled in his book “On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society,” which is on the curriculum of many American institutions. According to Grossman, in the realms of criminal justice, psychology, sociology, and peace studies programs, the possible existence of an innate resistance to killing, in most healthy citizens, is widely accepted[88][98][99].

There is some criticism towards Grossman as well. For example, his idea that video games make people more violent and train them to be killers has been shown to be unfounded. And his promotion of military training for police officers, including training them to kill, has been criticized for the fact that it could lead to more police violence against ordinary citizens[100][101][102][103][104]. But none of this is relevant to the current topic. Grossman may be a controversial person who is wrong about some things, but his position on the existence of resistance to killing is well-founded[Author's note].

Another criticism worth mentioning is put forward by anthropologist Michael Ghiglieri. He is a proponent of the idea that humans have an instinct to commit murder, rape, and genocide, developed over millions of years of evolution. And those who argue otherwise, including Grossman, in his opinion, simply do not understand biology. However, in a review of his book “The Dark Side of Man: Tracing the Origins of Male Violence,” anthropologist Brian Ferguson writes that it is full of arguments by analogy, sweeping generalizations, and one-sided presentations. It also contains major misinformation that is inconsistent with the literature on the topic of violence, according to which the decision to kill in men is triggered by just one chemical, testosterone. However, Ferguson praises Ghiglieri for skillfully writing his book to convince people already primed to believe men are bad to the bone[105][101][106]. Now, having dealt with the criticism, we can continue to explore the topic of resistance to killing.

Back in the middle of the 19th century, French army officer and military theorist Charles Ardant du Picq conducted his own research, a survey among other officers, who told him that many soldiers simply shot in the air without aiming[107]. Military historians John Keegan, Richard Holmes, and Paddy Griffith analyzed data on the firing performance of 18th- and 19th-century soldiers and showed that at the average combat ranges of that era, the killing rate should have been hundreds per minute, but in reality, only one or two killings occurred. The weak link between the killing potential and the killing capability was the soldier who, when faced with a living opponent instead of a practice target, simply fired over his head. Only a small percentage of soldiers were actually attempting to fire at the enemy[108][109][88].

The Battle of Gettysburg, the bloodiest battle of the American Civil War, is quite a demonstrative example. After the battle, more than 27,000 abandoned muskets were found, 90% of which were loaded, and 12,000 muskets were loaded multiple times. As Canadian historian, journalist, and retired naval officer Gwynne Dyer writes, this could mean that most of the soldiers on both sides were loading their muskets, perhaps even mimicking the act of firing when someone nearby actually did fire in order to hide their internal defection from the killing process but couldn't fire themselves. And many of those who did fire were probably deliberately aiming high[110][89]. Of course, some might say that the soldiers simply made mistakes when using weapons. But even if, despite all the endless hours of training, you do accidentally double-load a musket, you shoot it anyway, and the first load simply pushes out the second load. And in the rare event of a weapon breaking, you can pick up another one. It is therefore unlikely that a huge number of soldiers could have made the same mistake[88].

Dyer also cites one interesting fact from the statistics of the U.S. Air Force. Less than 1% of pilots accounted for about 40% of downed enemy aircraft. Most of the pilots didn't shoot down anyone and didn't even try to do it. In addition, when the U.S. Air Force tried to identify commonalities among their World War II aces, it was found that in childhood, they had been involved in a lot of fights. And they were not just bullies who, as a rule, avoid real fights; they were exactly “fighters”[111][88].

Looking back at how many victims some wars, and especially World War II, had, it is difficult to agree that only 2% of soldiers actually killed their enemies easily. However, this can be easily explained by distancing. Dyer notes that strong resistance to killing was not observed in artillerymen, bomber crew members, naval personnel, and machine gunners, who, without seeing their target (and whose task was to strike not living humans but non-living objects, even if that meant the attendant loss of life), were able to convince themselves that they didn't kill anyone at all[111][88].

It should also be noted that the training of soldiers after World War II began to consider the existence of resistance to killing. It was made more effective, “conditioning” soldiers to kill reflectively and automatically, so the number of soldiers firing in combat increased significantly (although this still doesn't tell us anything about how many of them actually aim at the enemy). And for some modern armies that rely on volunteers who are more susceptible to conditioning training than conscripts and weed out the unsuitable ones, it is not a problem to get 100% of soldiers to fire. However, soldiers who do find themselves capable of killing after such training are later unable to cope with what they have done and begin to suffer from psychological trauma[88][90][94][97].

According to some researchers, including Kevin Dutton, nowadays, psychopaths are extremely common among elite or special forces, where selection is deliberately focused on traits typical of psychopaths. Such individuals are characterized by high psychological stability and cold-bloodedness in military operations. But militarized groups consisting of psychopaths have a “culture of impunity” and are cold-blooded towards civilians. Therefore, they can easily kill peaceful and unarmed people in foreign operations, and authoritarian regimes can use them to effectively suppress internal discontent[112][113].

In the end, it is worth noting that there is a statement that roughly 80% of males choose to avoid violent conflict. If forced into violent conflict, they just do not fight, although present. The 20% left do not reject violence as a behavioral option. Nevertheless, the main part is probably defensive only, that is, they use violence only if compelled to. Finally, about 1% adopt an offensive elementary strategy. Historical and statistical facts confirm the existence of a ratio noncombatants : defensive combatants : offensive combatants. Roughly, this ratio looks like 80:19:1[89]. This statement is mentioned by researcher Johan M. G. van der Dennen, who has also done a good job collecting evidence on resistance to killing. However, its primary source is an “unpublished manuscript” that cannot be found. Therefore, we will leave it to your judgment[Author's note].

▶ See also: Documentary film "The Truth About Killing" (2004)

5. How many people participate in committing genocides

It is known that the Khmer Rouge exterminated about 1.8 million Cambodians between 1975 and 1979. Khmer Rouge forces consisted of 55 to 80 thousand people in different years. And the population of Cambodia was about 7.3 to 7.9 million people at the beginning of the genocide[114][115][116][117][118][119]. If we take the ratio of Khmer Rouge forces to the Cambodian population aged 15 to 64 (it was 55% of the total population), we will get that less than 2% of people were genocide perpetrators[Author's note].

Based on the most widely accepted studies, between 500,000 and 800,000 Tutsis were murdered in the Rwandan genocide[120][121]. And one study suggests that the number of genocidal murderers, consisting of Hutus, had to be 50,000 people. It also states that the genocide was not a spontaneous eruption of tribal hatred, as the Western media portrayed it; this was a coordinated attack by a small core with no more than two dozen leaders and no more than 100,000 of their henchmen in the state machinery (including the military)[122]. Another study estimates the number of genocide perpetrators (those who committed murder attempts, murder, rape, torture, and other forms of serious violence) from 175,000 to 210,000 people[123]. The maximum estimate of the number of people who committed at least one act of genocidal violence (including participating in groups that perpetrated genocide and complicity in acts of violence) reaches 234,000. And 90% of the participants were men with a median age of 34 years[124].

What does this mean? The vast majority of the Hutu people, and even the majority of their active adult (aged 18 to 54) male population, did not take any violent part in the genocide. It can be confidently stated that no more than 17% of the active adult male Hutu population (totaling 1.26 million people) and no more than 9% of the entire active adult Hutu population (totaling 2.58 million people) participated in the genocide. Although these are extremely high and extraordinary figures, there is still no question of a “criminal population” and collective guilt[123][124][Author's note].

It is worth noting some important considerations. The study estimating the number of murderers in the Rwandan genocide at 50,000 people states that it is not impossible that even 25,000 people could kill hundreds of thousands, if not a million civilians, in 100 days. For such a scenario to become a reality, one murderer needs to commit only one murder every two and a half days[122]. There is also evidence that in one of the Rwandan military camps, there were 2,000 well-trained soldiers, and of these, just 40 people could kill up to 1,000 Tutsis in 20 minutes[125].

In order to prove the ability of ordinary men to commit genocides, the example of Reserve Police Battalion 101, which consisted of less than 500 men and killed tens of thousands of Jews, is sometimes mentioned. As noted, the battalion was made up of very ordinary, middle-class men, which may indicate the capability of any group of men to become killers. However, it is important to note that even in this case, up to 20% of the battalion members had serious psychological difficulties in committing killings and eventually refused to do so. In addition, there is a view that questions the claimed “ordinariness” of this group of men and points to the need to find an abnormality that could explain this case[126][127].

Finally, it is important to note the cases where one individual personally killed thousands of people. For example, the Croatian war criminal Petar Brzica killed up to 1360 Serbs in one night[128]. And the NKVD officer Vasily Mikhailovich Blokhin executed up to 20,000 people in his entire service[129]. Such cases only confirm the fact that in the presence of an unlimited opportunity to murder, the murderers will personally commit dozens, hundreds, and possibly thousands of murders. Accordingly, we should always expect that the number of murderers relative to the number of murders will be quite small[Author's note].

6. What famous experiments say about violence

“Universe 25”

“Universe 25” was a famous experiment in which ethologist John Calhoun created a habitat for mice with abundant resources. Initially, the population of mice grew rapidly up to 2200 individuals. However, after that, mice began to refuse to reproduce; their numbers began to decline, and in less than 5 years, the population completely died out. Drawing an analogy to human society, Calhoun concluded that exceeding a certain population density leads to the degradation of the behavior of individuals, the breakdown of social bonds, and, later, the complete extinction[130].

This experiment was criticized for making many mistakes; for example, the mice's living conditions were actually far from ideal. However, few people are aware that the main mistake was the structure of the habitat, which allowed the 65 largest males to forcefully block all other males from accessing females and food. This caused a chain of events that led to the extinction of the population. A mouse population can live for decades in more well-organized habitats, where it is impossible to establish such a violent dominance hierarchy[131]. This experiment demonstrates well why, under certain conditions, violence is a threat to the survival of the population and is not an evolutionarily stable strategy[Author's note].

The Milgram experiment

In 1963, psychologist Stanley Milgram conducted experiments to clarify how much suffering ordinary people are willing to inflict on other, completely innocent people if it is part of their duties. The subject, being in the role of a “teacher,” had to punish the “learner” who was in the other room with an electric shock in cases of incorrect performance of tasks. Of course, being an actor, the learner only pretended to be in pain by knocking on the wall or screaming.

According to published data, one of the series of experiments showed that 26 subjects out of 40 (65%) increased the voltage to the maximum and did not stop delivering electric shocks until the researcher gave the order to end the experiment. And only 5 subjects (12.5%) stopped when the learner showed the first signs of discontent[132]. Reproduction of the experiment under different conditions and with different people, as stated, showed approximately the same results[133].

However, after analyzing 656 post-experimental questionnaires, the researchers found that 56% of the participants actually stopped the experiment at one point or another because they believed the person behind the wall was in pain. Another study, looking at 91 post-experimental interviews, found that among 46 participants who continued the experiment after the learner showed discontent, 33 participants (72%) did so because they simply did not believe that the experiment was real (and the learner actually only pretended to be in pain). Although Milgram himself recognized the dependence of the willingness to continue the experiment on belief in the reality of inflicting pain, for some reason, he chose not to publish the full results[134][135][136].

This experiment also had serious methodological problems. The researchers put strong pressure on the participants, often going beyond the protocol of the experiment. The professionalism of the actor who played the role of the learner is questionable. And the experiment was based on the deception of the subject, whereas there is reason to believe that unconsciously, most people would recognize real pain or its absence[137]. These problems also make any attempt to replicate the Milgram experiment questionable[Author's note].

The Stanford Prison Experiment

Another well-known experiment about violence is the Stanford Prison Experiment. The participants of this experiment were divided into two groups: the guards and the prisoners, who lived in a simulated prison. Soon after the start of the experiment, the guards began to brutally abuse the prisoners, with a third of them showing sadistic tendencies. Two prisoners were even removed from the experiment due to the psychological trauma they received, and the experiment itself was stopped ahead of time for ethical reasons.

For almost 50 years, many believed in the truthfulness of these results. However, the experiment turned out to be completely untenable. The guards were aware of the results that were expected from them and received clear instructions. Potential participants knew in advance what awaited them in the experiment and what roles they would play. And after a while, some of them stated that they only played their role and knew everything wasn't real. One of the excluded participants later admitted that he was only faking psychosis because he did not like the experiment and wanted to leave as soon as possible. Finally, the data researchers published were far from complete; out of the 150 hours of the experiment, only 10% were recorded (6 hours of video and 15 hours of audio)[138][139].

Other experiments on violence and conclusions about them

It is worth remembering another experiment, the performance of the artist Marina Abramovic called “Rhythm 0,” in which she completely surrendered to the will of the audience, allowing them to use 72 objects and her body freely. As a result, for 6 hours of the performance, she was brutally tortured and even almost shot. It was concluded that all people are cruel, and under suitable conditions, this cruelty will surely break out.

So far, there are no refutations of this experiment. But it can be assumed that it was either staged, like the Stanford prison experiment, with which it is sometimes compared, or the audience was unrepresentative, or cruel people were specially selected as the audience (in many of her performances, Abramovich deliberately put herself in danger and almost died several times)[Author's note]. At least Abramovich's past performances could determine the audience and its expectations[137]. Note that such assumptions can be put forward for any experiment that allegedly proves the violent nature and cruelty of a human being[Author's note].

There was also an anthropologist, Santiago Genovés, who believed humans were inherently cruel. To prove this, he placed 10 people of different genders, races, and social statuses with him on a small raft in the ocean. He expected an outbreak of violence to occur in such isolated conditions. However, in fact, no such thing happened, even when Genovés tried to provoke the participants. He was extremely dissatisfied with the outcome of his experiment[140]. He did not succeed in deceiving the public by adjusting the experiment to a predetermined result, as is usually done by those wanting to prove human cruelty[Author's note].

7. Violence draws too much attention to itself

Sometimes, it is stated that not a single day in human history has passed without violence and military conflicts. So, it should be a natural phenomenon for humans and human society. However, this opinion is based more on the subjective evaluation of events taking place in the world than on real data, as well as on the excessive visibility of violence against the background of all other events.

There is one illustrative example of how violence can attract significant attention: 69% of Americans believe that domestic violence is a common problem among American football players. This belief is based on media scandals unfolding around players who have actually committed violence. However, statistics show that in the families of American football players, domestic violence occurs almost 2 times less often than on average in American families. At the same time, there is a serious problem of domestic violence in the families of police officers; in them, it occurs up to 4 times more often than on average. But this is information that is often not publicized and investigated[141][142][143][144][145][146].

Observing violence makes people believe that it is common. However, to give a real assessment, one should rely only on real data and not on arbitrary statements[Author's note].

8. What fiction gets wrong about the nature of violence

Some fictional works can create the false impression that a peaceful person, totally incapable of committing violent attacks, must necessarily be a passive and unmotivated individual. Of course, aggressive stimulus can be important for an individual in many activities. There is even research demonstrating the beneficial role of anger in creative performance[147]. But one should not equate functional aggression with violence.

In Stanislaw Lem's “Return from the Stars,” in order to maintain a peaceful society, people are treated with a procedure called “betrization,” designed to neutralize aggressive impulses in the brain and strengthen the self-preservation instinct. But in reality, people do not necessarily need to have no aggressive impulses or strong fear for their lives to be absolutely peaceful and non-psychopathic. They only need to have strong reflexes and emotions that will impose inhibitory control on aggression (i.e., the violence inhibition mechanism), causing them to have an inner resistance to harming other people.

Another book called “A Clockwork Orange” by Anthony Burgess is based on the author's view that all human beings have an inner drive to commit violence, provoked by “original sin,” and to take away an individual's freedom to choose whether or not to commit violence is unacceptable. Obviously, a work based on a view that normalizes violence is not something we can take seriously. Many people have a strong inner resistance to committing violence, and they certainly do not look like the protagonist of this work after brainwashing that made him unable to defend himself and listen to his favorite music.

As we can see, fictional works' representations of the nature of violence can be extremely misleading. This is always worth mentioning when someone cites them as an argument[Author's note].

III. The Theory of the Violence Inhibition Mechanism

With plenty of evidence that, in many circumstances, aggressive behavior is restrained, and that people normally have a strong inner resistance to committing violence, we can proceed to an explanation of this phenomenon. To understand the evolutionary reasons for its emergence, we will first look at the theory of intraspecific aggression inhibitions in animals. Then, we will move on to the theory of the violence inhibition mechanism in humans.

1. Evolution of intraspecific aggression inhibitions

In interspecific interactions, for example, in predation and defense, the role of aggression is quite obvious. It is also important in intraspecific relationships, for example, in the division of territory, reproductive competition, and the establishment and maintenance of social hierarchy. Nevertheless, do not make the mistake of looking at aggression in isolation from evolutionary pressures. The two most important of them are the presence of strong innate weapons in conspecifics and their lack of opportunity to avoid each other (due to a limited area of habitat, social behavior, or other reasons). The more pronounced these two factors are, the greater the risks of aggressive behavior. As a result, its unrestrained forms cease to be an evolutionarily stable strategy of behavior as they begin to interfere with survival, and natural selection directs towards the development of strong restraints, preventing the infliction of serious harm and killing between conspecifics.

The concept of aggression inhibitions was first formulated by the ethologist Konrad Lorenz. According to his theory, they are most developed in animals, which are able to kill an individual of approximately their own size easily (with a single peck or bite). Describing his own observations of wolves, Lorenz showed how aggression inhibitions are activated when one wolf demonstrates to another a gesture of submission or vulnerable parts of its body, such as the neck or belly. As a result, a petrified aggressor cannot continue the attack. Also, observations of ravens showed that they do not peck out each other's eyes, even during fights[21][22].

To avoid any misunderstandings, it should be noted that wolves are sometimes considered to be animals with a violent dominance hierarchy in which the most aggressive male is in charge. However, in reality, such a hierarchy occurs only in artificial conditions, for example, in zoos, while in the natural environment, aggressive individuals are even expelled from the pack[148][149].

The ethologist Irenaus Eibl-Eibesfeldt listed many examples of aggression inhibitions from various researchers[23]. Fiddler crabs, due to their anatomical features, do not open their claws in fights wide enough to injure an opponent[150][151]. Many species of fish, lizards, and mammals are characterized by the ritualization of fights. A noteworthy example is oryx antelopes, which carefully handle their sharp horns in fights with other oryx but at the same time use them to the full extent in defense against lions[152]. It is also worth mentioning venomous snakes, many of which squirm, bloat, and push each other during fights but do not bite or even display their weapons[23][153]. Even very primitive creatures have a similar mechanism. So, jellyfish have a chemical blocker that prevents stinging a conspecific. At the same time, all other living beings are stung automatically[154].

Aggression is less inhibited in weakly armed species. Compared to ravens, turtledoves with a less sharp beak can even kill a conspecific if it is deprived of the opportunity to escape (for example, placed in a cage). Under natural conditions, conflicts do not threaten the survival of turtledoves in any way; they are unable to kill a conspecific quickly, and it can easily escape. Animals with a solitary lifestyle are also quite aggressive. For example, conflicts pose little threat to the survival of polar bears or jaguars, which, out of the breeding season, rarely cross each other's paths[21][22].

We should also not forget such a factor of selection against aggressive behavior as inclusive fitness. The basis of evolution is the preservation and spread of genes. And one and the same gene, carriers of which kill each other, has fewer chances for this. Accordingly, developing mechanisms that restrain aggression between individuals sharing enough of the same genes is evolutionarily beneficial. Among other things, inclusive fitness may be one of the evolutionary factors that led to the development of aggression inhibitions in humans, despite the fact that, according to Lorenz, due to weak innate weapons, humans have rather weak aggression inhibitions that do not cover the use of the artificial weapons they have created[21][27][155]. Lorenz was concerned about the consequences of humans becoming the most armed species on the planet. However, due to evolutionary reasons, the vast majority of humans cannot be psychopathic individuals. Such individuals are “freeriders” with a parasitic strategy, and human society is only able to exist if their number is limited. Otherwise, it will be destroyed by their actions, which is unprofitable even for the psychopaths themselves[85][156][157][158]. The average and healthy individual still has a strong inner resistance to killing, and “it gives us cause to believe that there may just be hope for mankind after all”[88].

It is necessary to take into account that some unknown and still unstudied factors can weaken aggression inhibitions, as it happens, for example, in lions, which are strongly armed and social species but still kill conspecifics[23]. Also, Lorenz's theoretical developments are sometimes criticized. For example, there is criticism of his hydraulic model of aggression, which states that living beings have a tendency to accumulate “aggressive energy” if there is no discharging stimulus for a long time, and later, it can be released in the form of aggressive behavior even from insignificant external stimulus provoking it; among other things, this explains spontaneous acts of aggression. However, Lorenz himself recognized the limitations of this model and that it has a number of shortcomings. In addition, there is a study confirming the existence of such a mechanism and even explaining its neurophysiology[22][159][160]. Lorenz may also be accused of labeling aggression as a universal and inevitable phenomenon for humans, but it is worth considering that in his works, he called intraspecific aggression the greatest danger to humanity and expressed optimism about the possibility of eradicating racism and stopping wars. And the criticism of Lorenz's works does not concern his theory of aggression inhibitions[22][40][Author's note].

Finally, it is necessary to mention the parochial altruism hypothesis. Based on it, intragroup altruism and intergroup hostility have mutually developed during biological evolution and exist side by side[161][162]. This phenomenon may be argued to contradict the theory of intraspecific aggression inhibitions. However, one study shows that it only explains defensive aggression when there is an imminent threat from competing groups but is not necessarily associated with offensive aggression toward them[163]. We will address the issue of parochial altruism again in the fifth topic of Chapter Four. For now, it is only important to understand that in the case of humans, intermarriage and trade would have been impossible without inhibition of intergroup killing, and “preliterate” societies would have been locked in eternally hostile and xenophobic isolation, killing any “stranger” on sight[89].

2. Self-defense as an evolutionarily stable strategy of behavior

As we discovered earlier, committing violent attacks on conspecifics is not an evolutionarily stable strategy of behavior for animals that have strong innate weapons and lack the opportunity to avoid members of their own species. The most aggressive individuals, often initiating violent attacks, will also die more often due to the weapons and resistance of their victims. As a result, there will be evolutionary pressure to develop intraspecific aggression inhibitions or so-called violence inhibitor since individuals lacking such a mechanism are less likely to pass their genes on. However, it is worth understanding one important thing: this will not work if the victim of the attack cannot use their weapons in self-defense. This leads us to the assumption that in the presence of an immediate threat to life, the function of the violence inhibitor should be suppressed for a short period of time, sufficient to fight back against the aggressor[Author's note].

This assumption is consistent with the concept of the threat superiority effect, which we considered at the beginning of our study. According to it, the presence of a threat in the environment and social signals leads to the activation of defense mechanisms and the suppression of other ongoing cognitive processes. In behavior, this effect is often manifested by a fight-or-flight response[8][9][10]. Also, computer simulations of evolutionary processes have shown that in most cases, neither the belligerent strategy (hawk), which consists in making attacks, nor the timid strategy (dove), which consists in retreating when attacked, are not as evolutionarily stable strategies as the retaliator strategy, which means to behave non-aggressively but in the event of an attack to fight back. Timid individuals cannot compete with aggressive individuals, but aggressive individuals risk getting hurt in fights. Therefore, the mixed retaliator strategy is the most stable[164][165][166][28].

3. The Violence Inhibition Mechanism in Humans

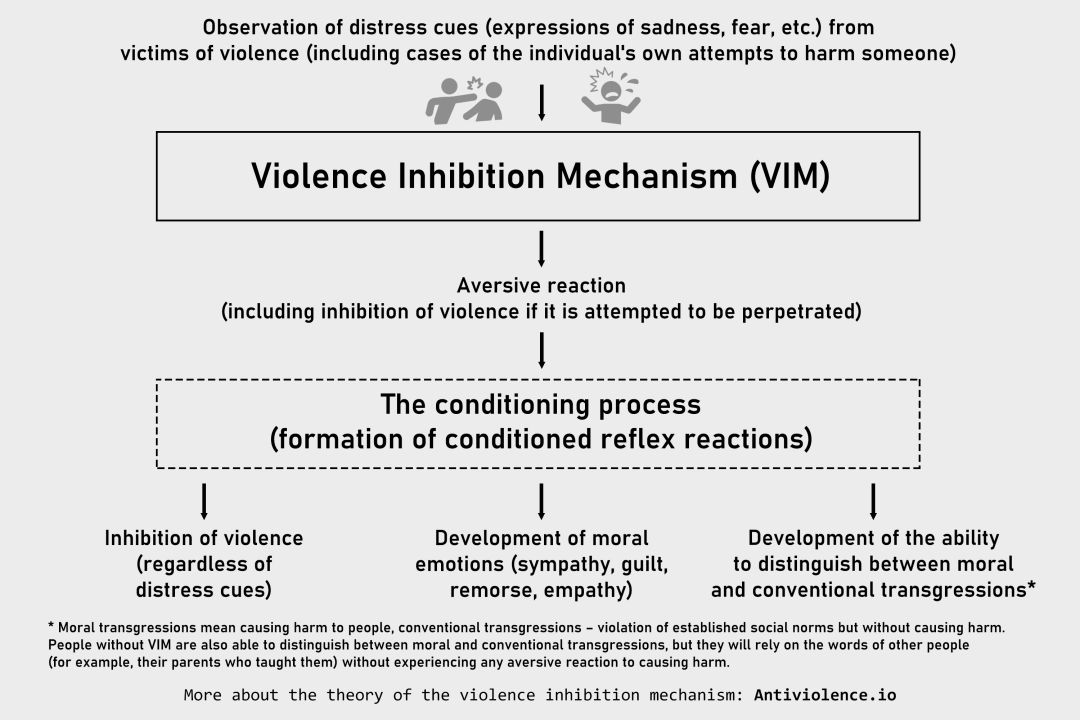

Neuroscientist James Blair suggested that humans possess aggression inhibitions similar to those observed in many animals in intraspecific relationships and proposed the Violence Inhibition Mechanism (VIM) model. In developing the VIM model, he also aimed to explain the development of empathy as a result of this mechanism functioning and the emergence of psychopathy as a result of its dysfunction[167][168].

VIM is a cognitive mechanism that is directly activated by the observation of non-verbal distress cues from other individuals, such as a sad facial expression or crying. This causes an aversive reaction, and the stronger the distress cues, the stronger the corresponding reaction: a slight sadness on the face will cause only partial aversion, but screams and sobbing can completely stop the aggressor. Also, VIM is not just a mechanism consisting of an unconditioned reflex (aversive reaction) triggered by an unconditioned stimulus (distress cues). Blair argues that through the process of conditioning (the formation of conditioned reflexes), it becomes a cognitive prerequisite for the development of three aspects of morality: the moral emotions (i.e., sympathy, guilt, remorse, and empathy), the inhibition of violence (regardless of distress cues), and the ability to distinguish between moral and conventional transgressions.

During normal development, regular activation of the VIM on the observation of distress cues leads to the formation of corresponding conditioned reflexes. As a result, the individual becomes able to show an empathic response only by thinking about someone else's distress. Accordingly, during the experiments, film sequences where the victims of violence talked about their experience while not showing any distress cues induced physiological arousal changes in observers[169][170][171][168].

The inhibition of violence works similarly. As early as childhood (at the age of 4–7 years), normally developing individuals will experience the activation of VIM due to the observation of distress cues as soon as they attempt to commit an act of violence (or even take possessions from another child without their permission)[172]. Over time, even the very thought of committing violence will begin to lead to this reaction, and the probability that the individual will behave violently will gradually decrease.

The activation of VIM also acts as a mediator in distinguishing between moral and conventional transgressions. The observation of moral transgressions – actions that harm people – and the subsequent victims' distress cues will eventually lead to the development of the conditioned reflex that activates VIM. In turn, social transgressions that do not lead to harm but only consist in violating established social norms will not be associated with distress cues. This is how the individual becomes capable of identifying moral transgressions in various actions. Of course, individuals without VIM can evaluate a moral transgression as a bad act if someone teaches them that it is bad. However, in their evaluation, they will refer to the words of other people without experiencing an aversive reaction to causing harm.

To support the validity of his model, Blair cites the results of many studies. Children with a predisposition to psychopathy and adult psychopaths do show a poor ability to distinguish between moral and social transgressions. The same applies to children with conduct disorders. In addition, and in line with the VIM position, adult psychopaths show reduced comprehension of situations likely to induce guilt. Moreover, children and adults with psychopathy show pronounced impairments in processing sad and fearful facial and vocal expressions[168][173][174][175][176][177][178][179][180][181][182][183][184][185].

Other studies also support this model. For example, aggressive behavior from callous and unemotional traits, the presence of which in childhood is a prerequisite for psychopathy in adulthood, is associated with a poor ability to recognize fearful facial expressions and fearful body postures[186]. Children with high scores of сallous-unemotional traits also experience problems in recognizing expressions of sadness, and children with conduct disorder experience problems in recognizing expressions of fear[187]. People with high scores of primary psychopathy (which is characterized by callousness and lack of empathy) were found to be less able to distinguish genuine distress cues from posed ones. At the same time, this effect did not extend to other emotions, such as happiness, anger, or disgust; it was specific to distress cues[188]. Schizophrenics with a history of violent crime differ from non-violent schizophrenics in their lower ability to recognize expressions of fear[189]. Even the most up-to-date research shows that difficulties in recognizing fear and sadness are associated with a greater propensity for proactive (instrumental) aggression in children[190].

Finally, it is worth noting that psychopathy as a result of VIM dysfunction is a mental disorder by Wakefield's criteria: a condition is a disorder if it leads to harm to oneself or others and is associated with the failure of some internal mechanism to perform a function for which it was biologically designed (i.e., naturally selected)[191][192].

The VIM model does not provide a complete explanation of the nature of aggression regulation, so Blair later expanded it and developed the Integrated Emotion System (IES) model, which considers the neurophysiology of this process[173]. However, it still confirms the presence of aggression inhibitions in humans and gives a general idea of how they work[Author's note].

▶ See also: The problem of indirect violence; The ability to experience empathy and take the perspective of other people in psychopathic individuals; Violence inhibitor dysfunction is a cause of abusive relationships

IV. Neurophysiology and genetics of aggression regulation

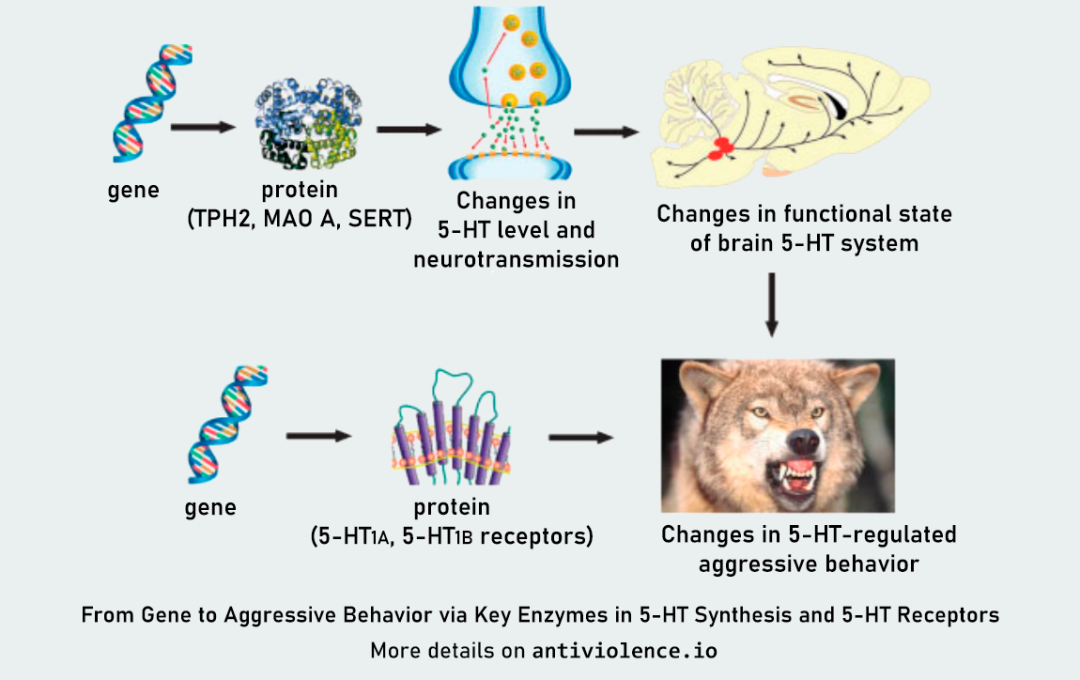

For a more in-depth understanding of how aggressive behavior is regulated, it is necessary to examine this process from a neurophysiological and genetic perspective. Among other things, this is particularly important in identifying a direction for the development of therapeutic approaches aimed at treating violence inhibitor dysfunction in individuals who have psychopathic tendencies and can easily harm others.

1. Serotonin: a key regulator of aggressive behavior and a target for its treatment

One study on moral judgments and behavior suggests that a mechanism similar to Blair's violence inhibitor operates for imagined harm. The neurotransmitter serotonin (5-HT) is responsible for the functioning of this mechanism and plays a parallel role in the inhibition of actual harm (in the case of aggression) and imagined harm (in the case of moral judgments)[193]. Many other studies also confirm the key role of serotonin in the regulation of aggression in animals and humans[194][195][196].

The administration of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which increase serotonin levels in the brain and are widely used as antidepressants, has shown interesting results in the issue of aggression[197]. Fluoxetine administration reduces the risk of aggressive behavior by 4 times in patients with personality disorders[198]. Also, in one trial, fluoxetine significantly reduced the perpetration of violence by alcoholics toward their spouses or significant others[199]. In another trial, paroxetine successfully eliminated aggression associated with primary psychopathy (which is characterized by callousness and lack of empathy). And it was found that this did not result from sedative or anxiolytic effects. Researchers believe that primary psychopathy is related to dysfunction of the serotonergic system of the brain[200]. Sertraline has been tested on violent repeat offenders and found to be effective in correcting their behavior[201]. Additionally, in several experiments, citalopram improved the ability of participants to recognize facial expressions of fear (as we remember, recognizing distress cues from other people is important in the functioning of the violence inhibitor), increased their generosity, and made them more likely to choose to avoid hurting people in certain types of moral dilemmas (indicating increased harm inhibition)[202][203][204][205]. However, SSRIs can lead to unwanted side effects[206]. Therefore, we will also review potentially more effective and safer drugs.

Various experiments conducted on mice and rats showed that some agonists of 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B receptors (these chemical compounds cause a biological response in receptors or, put simply, activate them) are able to suppress offensive aggression while not affecting defensive behavior or other forms of activity[207].

Drugs such as TFMPP and eltoprazine significantly reduced aggressiveness in mice and rats in the resident-intruder paradigm while not affecting defensive behavior. This effect was associated with the activation of postsynaptic 5-HT1B receptors[208]. In limited human trials, eltoprazine resulted in a reduction of aggression in patients with dementia, psychotic and personality disorders, and mental retardation, with it working best in severely aggressive patients and side effects being minimal or absent at all[209][210]. A selective 5-HT1A agonist called F15599 reduced the manifestation of intense elements of aggression, biting during attacks, and lateral threat postures (demonstrating aggressive intentions) in mice without affecting non-intense elements of aggression and other forms of behavior[211]. A 5-HT1B agonist called CP-94253 also reduced the frequency of attack bites and the manifestation of lateral threat postures in mice[212]. The importance of 5-HT1B receptors in the inhibition of aggression was also demonstrated in an experiment where the administration of their agonist anpirtoline reduced the manifestation of various forms of aggression in mice, including aggression from social interaction with an opponent and aggression from frustration[213]. Compared to other 5-HT1A agonists, a drug called alnespirone showed a highly selective anti-aggressive effect in rats, which did not affect the defensive behavior when the individual encountered an aggressive conspecific and other forms of activity[214].

It is known that psychedelics that are agonists of 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors, such as LSD and psilocybin (the latter is also a 5-HT1B agonist), can stimulate empathy and prosocial behavior in humans. In one experiment, psilocybin even led to a sustained reduction in patients' predisposition to authoritarian political views (as measured by the Libertarian-Authoritarian Questionnaire), and it is considered to be very useful in treating psychopathy and antisocial behavior[215][216][217][218][219][220]. Also, any experience using LSD or psilocybin reduces males' risk of committing intimate partner violence by 2 times[221]. In addition, any experience using psychedelics, as shown in a study of criminal behavior among 480,000 American adults, reduces the risk of committing violent assaults (and psilocybin has a particular protective effect against antisocial criminal behavior)[222]. A study of substance use among 211,000 American adults shows a similar result: any experience using psilocybin (but not LSD) is associated with a significantly reduced risk of committing violent crimes, especially serious ones such as rape and homicide[223]. Psychedelics, especially psilocybin, are also actively discussed in the issue of moral bioenhancement, which implies the use of biomedical technologies for the moral improvement of people[224][225].

Importantly, experiments on the treatment of hostility and aggression in violent offenders with naratriptan, which is a full agonist of 5-HT1B/1D receptors and a partial agonist of 5-HT1A receptors, were once suggested[226]. And the similar drug called zolmitriptan was successful in selectively reducing aggression in mice and attenuating alcohol-heightened aggression in humans[227][228]. It has also been suggested that vortioxetine, which is a full agonist of 5-HT1A receptors and a partial agonist of 5-HT1B receptors, may be an effective anti-aggressive agent. This is supported, among other things, by preliminary results obtained on a small number of patients[196][229]. Of course, vortioxetine is also an SSRI, but due to its multimodal mechanism of action, some researchers consider it safer and more effective than other SSRIs[230][231].

Some drugs similar to SSRIs may also have anti-aggressive effects. For example, in several trials, trazodone effectively reduced aggressiveness in children with disruptive behavior, and serious side effects were rarely observed[232][233]. Also worth considering is amitriptyline, which can eliminate aggressiveness in animals (without causing side effects or interfering with sex drive), as well as in children with behavioral disorders (although, in their case, frequent dosage changes are necessary due to the risk of side effects)[234][235][236].

Lithium has been actively studied in the correction of violent and antisocial behavior. As a result of an experiment conducted on 27 aggressive prisoners, 14 of them showed significant improvements in behavior, and 7 showed minor improvements. Lithium enhanced the ability to control anger and understand the consequences of aggressive actions toward other people[237]. In another experiment, lithium significantly reduced aggression in 16 out of 20 children with conduct disorder[238]. Studies conducted in various countries have linked higher concentrations of lithium in drinking water (from 70 μg/liter) with lower levels of crime, including violent crime and homicide[239][240][241]. The mechanism of action of lithium is not fully understood, but it is known to stabilize serotonin neurotransmission[242].

Some natural remedies are also worth mentioning. For example, a herbal extract mixture called Kamishoyosan reduces aggressiveness in mice, and this effect is associated with the activation of 5-HT1A receptors and improvements in the regulation of the serotonergic system[243]. It is known that its active component is peoniflorin from extracts of Paeonia lactiflora and Paeonia suffruticosa[244]. The Yokukansan mixture with a similar mechanism of action leads to a selective anti-aggressive effect in mice. It was found that the active ingredient in this mixture is geissoschizine methyl ether from the extract of Uncaria rhynchophylla[245]. Linalool, which is a component of many essential oils and a 5-HT1A agonist, also reduces aggressiveness in animals (including through inhalation of its vapors)[246][247][248]. In addition, essential oils may be effective in reducing aggressiveness in people with cognitive impairment[249].

Finally, supplementation with tryptophan, a precursor to serotonin, may be potentially effective. In experiments on mice and dogs, tryptophan had a selective anti-aggressive effect[250][251]. And in some human trials, it reduced aggressiveness and hostility and increased trust and generosity[252][253][254][255][256]. Also, tryptophan deficiency in the organism is associated with increased aggressiveness[257]. Certain probiotics (including various bifidobacterium and lactobacillus) may help increase tryptophan and serotonin levels in the organism. Among other things, they may influence the serotonergic system of the brain through the gut-brain axis[258][259][260][261][262][263]. The possibility of using them for the treatment of violent behavior is already being researched[264].

▶ See also: The history of the development of anti-aggressive agents for clinical use; Potentially effective treatment of violent behavior in humans

2. What brain regions are involved in the regulation of aggression

The amygdala, which is involved in emotional processing and aversive conditioning, and the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (or orbitofrontal cortex), which is involved in decision-making, play the main role in the regulation of aggression. Together, they modulate the neural circuitry mediating reactive aggression (this circuitry includes the medial hypothalamus and periaqueductal gray) and the subcortical systems responding to threats (among them, the basal ganglia, including the striatum). Both impairments in the amygdala and the orbitofrontal cortex can lead to an increase in the level of reactive aggression. At the same time, the orbitofrontal cortex does not inhibit reactive aggression but only increases or decreases the chance of triggering this process, depending on social cues. The neural circuitry mediating proactive (instrumental) aggression is modulated by the amygdala (it includes the temporal lobe, which processes information, as well as the striatum and premotor cortex, which are necessary for the implementation of actual behavior)[265][173].